Minimax-based AI for the Tic-Tac-Toe game in Scala

This article contains a brief introduction of the Minimax principle, together with minimalistic and pure functional implementation of the Minimax algorithm in Scala for the purpose of creation of the unbeatable Tic-Tac-Toe program.

Minimax Principle

Tic-Tac Toe belongs to the class of games, where two players compete against each other with strictly opposite interests, so the win of one player means the lose of another player.

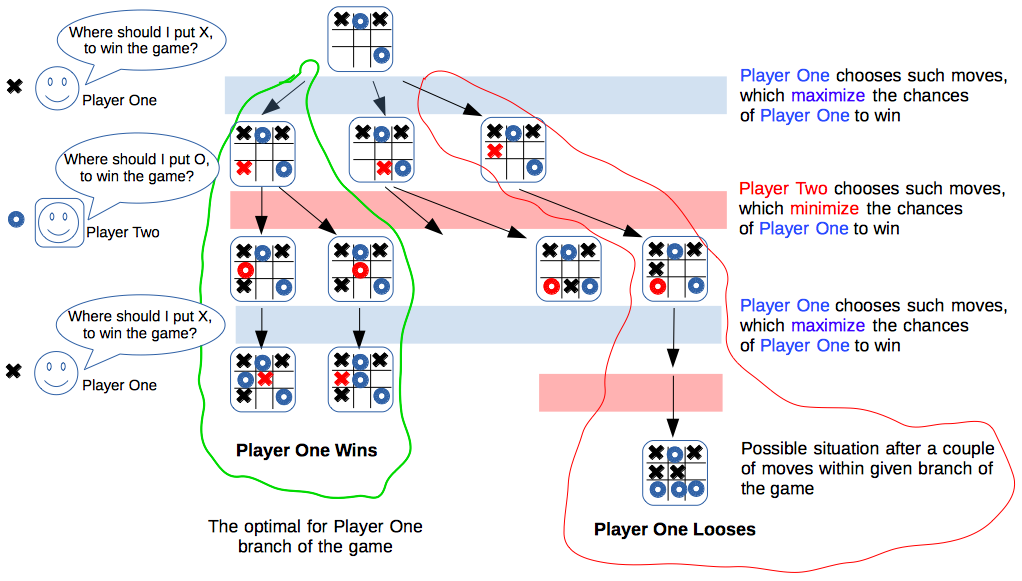

A rational choice of the actions of the players during such kind of games is based on the maximization of the "chances to win". However, taking into account that there are only two players, the objectives of the players can be redefined in a following way:

- the first player wants to maximize its own chances to win

- the second player wants to minimize the chances of the opponent to win

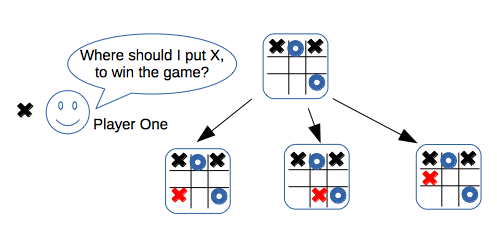

How can the first player choose the best move, given the current state of the game?

The optimal strategy would be to choose such move, which maximizes the chances to win, even in case if the second player will make the best possible move afterwards.

The similar strategy is optimal for the second player as well: it is needed to choose such move, which minimizes the chances of the first player to win, even if the first player will make the best possible move afterwards.

Hence, in order to choose the best move, the first player should consider all possible moves, and in order to evaluate the chances of win after each particular move - it is needed to estimate which move the opponent will do afterwards. However, the opponent will make the decision about the optimal move, based on the similar logic (based on the further optimal decision of the first player), and so forth.

Thus, the logic of evaluation of the optimality of move can be represented as a tree of game states, where each move represented as an edge, in combination with mutually alternating decisions regarding the optimality, depending on which player makes a move (e.g.: "maximization of chances of the first player to win" -> "minimization of chances of the first player" -> "maximization of chances of the first player" -> ... -> until the end of the game).

Described strategy is known as a Minimax principle.

Below presented a schematic example of the Minimax tree for the instance of the Tic-Tac-Toe game:

Minimax Algorithm in Scala

Let's implement the described Minimax strategy in Scala.

1) The trait which represents the state of the game:

trait State[S <: State[S]] {

def isGameOver : Boolean

def playerOneWin : Boolean

def playerTwoWin : Boolean

def isPlayerOneTurn : Boolean

// generates all possible states

// which can be produced from

// the current state of the game

def generateStates : Seq[S]

}2) The trait which represents the algorithm for finding the optimal move for the given state of the game:

trait BestMoveFinder[S <: State[S]] {

// produces the state, which represents

// the most optimal move for the given

// state of the game

def move(s: S): S

}3) Implementation of the Minimax strategy for finding of the best move:

class MinMaxStrategyFinder[S <: State[S]] extends BestMoveFinder[S] {

// Here, and in other methods

// parameter s - is a current state of the game

def move(s: S): S =

if(s.isPlayerOneTurn) firstTurn(s).state

else secondTurn(s).state

def secondTurn(s: S): Outcome =

bestMoveFinder(minimize, firstTurn, PLAYER_ONE_WIN, s)

def firstTurn(s: S): Outcome =

bestMoveFinder(maximize, secondTurn, PLAYER_ONE_LOOSE, s)

def bestMoveFinder(strategy: Criteria, opponentMove: S => Outcome,

worstOutcome: Int, s: S): Outcome =

if(s.isGameOver) Outcome(outcomeOfGame(s), s)

else s.generateStates

.foldLeft(Outcome(worstOutcome, s)){(acc, state) => {

val outcome = opponentMove(state).cost

if(strategy(outcome, acc.cost)) Outcome(outcome, state)

else acc}}

def outcomeOfGame(s: S): Int =

if (s.playerOneWin) PLAYER_ONE_WIN

else if(s.playerTwoWin) PLAYER_ONE_LOOSE

else DRAW

case class Outcome(cost: Int, state: S)

val PLAYER_ONE_WIN = 1 // the outcome, when first player wins

val PLAYER_ONE_LOOSE = -1 // the outcome, when second player wins

val DRAW = 0 // the outcome, when nobody wins

type Criteria = (Int, Int) => Boolean

def maximize: Criteria = (a, b) => a >= b

def minimize: Criteria = (a, b) => a <= b

}As you can see, the algorithm is implemented in a pure functional style without usage of mutable state.

Tic-Tac-Toe game in Scala

Now, everything is ready for implementation of the the unbeatable Tic-Tac-Toe program.

We have to implement the class, which can describe the instance of the Tic-Tac-Toe game. Tic-Tac-Toe game board consists of 3x3 cells, which are all empty at the beginning of a game, and at each step players can choose empty cell and populate it with the figure of the player (either 'X' or 'O').

One of the natural ways to model the game, is based on three sets:

- set of available cells

- set of cells, populated by the first player

- set of cells, populated by the second player

Also, at every step of the game, we should know whose turn is to make a move, so this information should be included into the state of the game as well:

// The utility class, just for the sake of possibility

// to manipulate conveniently with cells of the game board

case class Position(val row: Int, val col: Int)

class TicTacToeState(val playerOnePositions : Set[Position],

val playerTwoPositions : Set[Position],

val availablePositions : Set[Position],

val isPlayerOneTurn : Boolean,

// length of the sequence to win

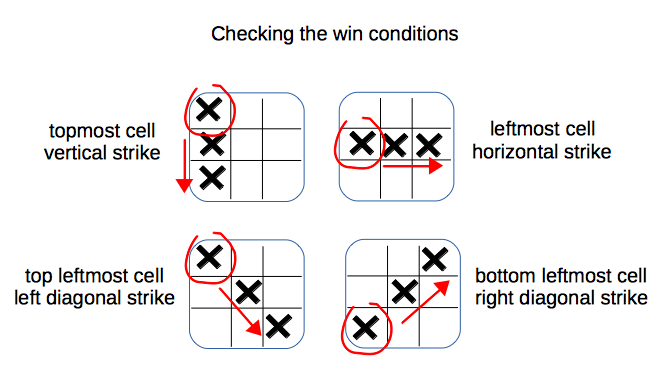

val winLength : Int) extends State[TicTacToeState]The winner is a player, which has populated the continuous sequence of cells with its figures (either vertical, or horizontal, or left diagonal, or right diagonal).

In case if player wins there always exists either the topmost, or the leftmost, or the top-leftmost, or the bottom-leftmost cell, starting from which all positions are populated by the figures of the player:

Below is the full source code of the TicTacToeState class:

case class Position(val row: Int, val col: Int)

class TicTacToeState(val playerOnePositions : Set[Position],

val playerTwoPositions : Set[Position],

val availablePositions : Set[Position],

val isPlayerOneTurn : Boolean,

val winLength : Int) extends State[TicTacToeState] {

lazy val isGameOver : Boolean =

availablePositions.isEmpty || playerOneWin || playerTwoWin

lazy val playerOneWin: Boolean = checkWin(playerOnePositions)

lazy val playerTwoWin: Boolean = checkWin(playerTwoPositions)

def generateStates: Seq[TicTacToeState] =

for(pos <- availablePositions.toSeq) yield makeMove(pos)

def makeMove(p: Position): TicTacToeState = {

assert(availablePositions.contains(p))

if(isPlayerOneTurn)

new TicTacToeState(

playerOnePositions + p,

playerTwoPositions,

availablePositions - p,

!isPlayerOneTurn,

winLength)

else new TicTacToeState(

playerOnePositions,

playerTwoPositions + p,

availablePositions - p,

!isPlayerOneTurn,

winLength)}

def checkWin(positions: Set[Position]): Boolean =

directions.exists(winConditionsSatisified(_)(positions))

final val directions = List(leftDiagonal, rightDiagonal, row, column)

type StepOffsetGen = (Position, Int) => Position

def leftDiagonal : StepOffsetGen =

(pos, offset) => Position(pos.row + offset, pos.col + offset)

def rightDiagonal : StepOffsetGen =

(pos, offset) => Position(pos.row - offset, pos.col + offset)

def row : StepOffsetGen =

(pos, offset) => Position(pos.row + offset, pos.col)

private def column : StepOffsetGen =

(pos, offset) => Position(pos.row, pos.col + offset)

def winConditionsSatisified(step: StepOffsetGen)

(positions: Set[Position]): Boolean =

positions exists( position =>

(0 until winLength) forall( offset =>

positions contains step(position, offset)))

// Just additional constructor for convenience

def this(dimension: Int, winLength: Int) = this(

Set(), Set(), // positions of the players are empty initially

(for{row <- (1 to dimension) // initialize available positions

col <- (1 to dimension)} yield Position(row, col)).toSet,

true, winLength)

}Human-driven BestMoveFinder

In order for being able to play with computer, we need to define an implementation of the BestMoveFinder, which will ask user to input the coordinates of the next move:

class HumanTicTacPlayer extends BestMoveFinder[TicTacToeState] {

def move(s: TicTacToeState): TicTacToeState = {

println("Input the row and the column, please:")

val (row, col) = readf2("{0, number} {1,number}")

val pos = Position(row.asInstanceOf[Long].toInt, col.asInstanceOf[Long].toInt)

try {

s.makeMove(pos)

} catch {

case _: Throwable => {

println("Such move is impossible!")

move(s)}}}

}Tic-Tac-Toe game driver

Below is a source code of the Tic-Tac-Toe game driver, which requires two instances of the BestMoveFinder as the arguments of constructor (so we could arrange either human-computer, or human-human, or even computer-computer games):

class TicTacToe(playerOne: BestMoveFinder[TicTacToeState],

playerTwo: BestMoveFinder[TicTacToeState]) {

private var players = List(playerOne, playerTwo)

private var game: TicTacToeState =

new TicTacToeState(DIMENSION, DIMENSION)

def play = {

var moveNumber = 0

while(!game.isGameOver) {

println(s"Player ${moveNumber % 2 + 1} makes move:")

val player = players.head

game = player.move(game)

println(display(game))

players = players.tail :+ player

moveNumber += 1

}

if(game.playerOneWin) println("Player One win!")

else if(game.playerTwoWin) println("Player Two win!")

else println("Draw!")

}

def display(game: TicTacToeState) =

(1 to DIMENSION).map(row =>

(1 to DIMENSION).map(col => {

val p = Position(row, col)

if(game.playerOnePositions contains p) X_PLAYER

else if(game.playerTwoPositions contains p) O_PLAYER

else EMPTY_CELL

}).mkString).mkString("\n") + "\n"

final val DIMENSION = 3

final val X_PLAYER = "X"

final val O_PLAYER = "O"

final val EMPTY_CELL = "."

}Some mutable variables have been used inside, which was done just for the sake of conciseness of the code.

Human vs. Computer game

Below is presented the setup for the human vs. computer game (Player One is a human, Player Two is the Minimax-based best move finder):

object Demo extends Application {

val game = new TicTacToe(

new HumanTicTacPlayer(),

new MinMaxStrategyFinder[TicTacToeState]())

game.play

}The log of the game:

Player 1 makes move:

Input the row and the column, please:

3 3

...

...

..X

Player 2 makes move:

...

.O.

..X

Player 1 makes move:

Input the row and the column, please:

3 1

...

.O.

X.X

Player 2 makes move:

...

.O.

XOX

Player 1 makes move:

Input the row and the column, please:

1 1

X..

.O.

XOX

Player 2 makes move:

X..

OO.

XOX

Player 1 makes move:

Input the row and the column, please:

1 3

X.X

OO.

XOX

Player 2 makes move:

XOX

OO.

XOX

Player Two win!The code is available on GitHub: https://github.com/lagodiuk/tic-tac-toe-minimax-scala