Random walks in a hexagon

There is a hexagon and a traveller, which moves between vertices of the hexagon. At every step the traveller randomly chooses one of adjacent vertices and moves there. The question is: how many paths are there - which end in the initial vertex after N steps?

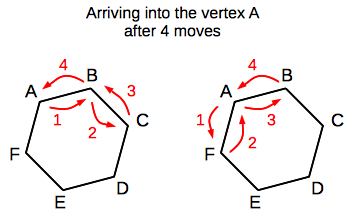

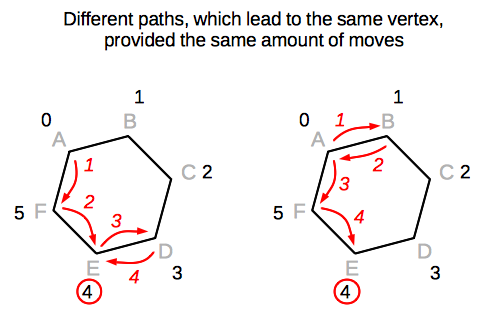

For the sake of convenience, let's assign letters to the vertices of the hexagon, and let's assume that initial vertex is "A". Below is an illustration, which demonstrates two paths (out of six possible), which end in the initial vertex after four steps (the arrows are indexed in the order of performed moves):

I will describe a couple of algorithms for tackling described problem, we will see how the runtime efficiency of solutions can be improved from an exponential complexity down to almost a constant time complexity. And, finally, we will discuss the pros and cons of each approach.

- Brute-force solution

- Dynamic programming solution

- Derivation of a simpler recurrence relation

- Conclusion

- Source of the problem

Brute-force solution

Let's start with a Brute-force solution.

As an auxiliary step, let's assign indices to the vertices of the hexagon (from the interval 0 to 5).

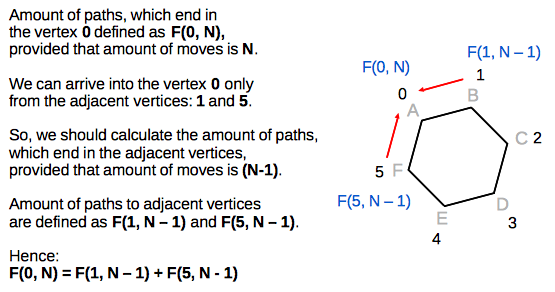

We can observe that an amount of paths, which end in any specific vertex,

depends only on the amount of paths to adjacent vertices:

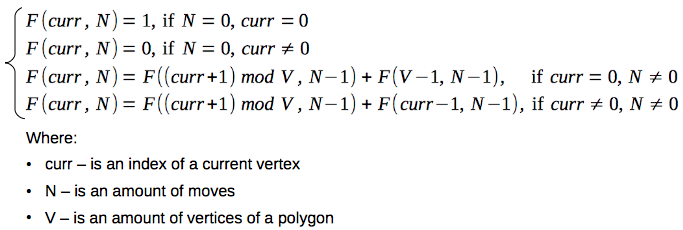

So, based on the described observation, we can derive the following recurrence relation:

Which can be straightforwardly implemented as a recursive function:

// amount of vertices of the polygon

final int V = 6;

int solve(int moves) {

return F(0, moves);

}

// curr - index of a current vertex

// moves - amount of moves

int F(int curr, int moves) {

if(moves == 0) {

return (curr == 0) ? 1 : 0;

} else if(curr > 0) {

return F((curr + 1) % V, moves - 1)

+ F(curr - 1, moves - 1);

} else {

return F((curr + 1) % V, moves - 1)

+ F(V - 1, moves - 1);

}

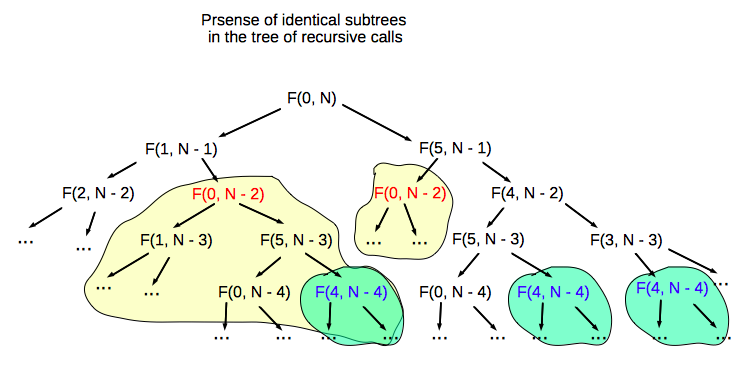

}However, the analysis of the tree of recursive calls shows, that there are many identical subtrees:

The presence of identical subtrees of recursive calls, is a result of a fact, that it is possible to arrive in a vertex via different paths, using the same amount of moves:

So we see, that the solution of the problem consists of solutions of the overlapping subproblems.

As far as described thoughts are valid for every value of N (amount of moves) - we can conclude, that the solution of every instance of the problem consists of the solutions of overlapping subproblems. Hence, using the reasoning based on induction we can conclude, that the overall complexity of described solution is exponential.

Actually, the brute-force solution is too impractical even for middle-sized instances of the problem.

Dynamic programming solution

As far as the recursive solution consists of the overlapping problems, let's calculate the size of the space of subproblems.

The recursive function F has two arguments:

int moves- amount of available moves, which varies from 0 to Nint curr- index of a current vertex, which varies from 0 to (V - 1)

So, as far as the combination of values of the arguments of function F uniquely determines a subproblem - the total amount of subproblems is (N+1) * V.

Hence, we can make use of the memoization table (with dimensions (N+1) x V) in order to store the values of already solved subproblems:

// amount of vertices of the polygon

final int V = 6;

// Needed for memoization

final int NOT_SOLVED_YET = -1;

int solve(int moves) {

// Initialization of the memoization table

int[][] memoized = new int[moves + 1][V];

for(int[] row : memoized) { Arrays.fill(row, NOT_SOLVED_YET); }

return F(0, moves, memoized);

}

int F(int curr, int moves, int[][] memoized) {

// Is the subproblem already solved?

if(memoized[moves][curr] != NOT_SOLVED_YET) {

return memoized[moves][curr];

}

int result;

if(moves == 0) {

result = (curr == 0) ? 1 : 0;

} else {

if(curr > 0) {

result = F((curr + 1) % V, moves - 1, memoized)

+ F(curr - 1, moves - 1, memoized);

} else {

result = F((curr + 1) % V, moves - 1, memoized)

+ F(V - 1, moves - 1, memoized);

}

}

// Remember the solution of the subproblem

memoized[moves][curr] = result;

return result;

}Provided recursive algorithm is a Top-down version of the Dynamic programming solution. It can be rewritten into the iterative algorithm (a Bottom-up version of the Dynamic Programming solution). Inside the iterative solution - it is not needed to keep the entire memoization table, and instead we can track only the previous row of the table, which helps to reduce the memory footprint of the solution.

As far as in a worst case it is needed to traverse an entire memoization table in order to solve the problem - the complexity of the Dynamic programming solution is O(N * V).

Taking into account that V (amount of vertices) is a constant - the complexity of solution is linear in terms of N: O(N).

For the sake of curiosity let's look on the table of solutions of the small instances of the problem:

| Amount of steps | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount of paths | 0 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 86 | 0 | 342 | 0 | 1366 | 0 | 5462 | 0 | 21846 | 0 | 87382 | 0 | 349526 | 0 | 1398102 |

Observe, that for all odd values of N the solution is zero.

Derivation of a simpler recurrence relation

Is it possible to develop a solution with better runtime complexity?

It turns out that yes. However, we will need a bit of the extra math in order to reveal the insights regarding the structure of problem.

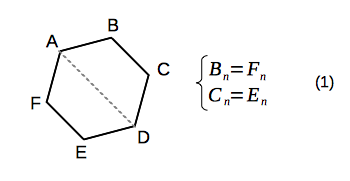

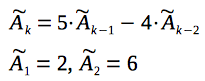

Let's introduce an auxiliary notation (keeping in mind, that we consider only paths, which starts in the vertex "A"):

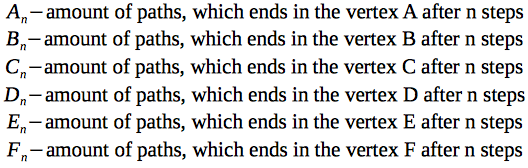

The presence of the symmetry axis (which goes through the starting vertex "A") of hexagon implies:

Let's write recurrence relations for calculations of amount of paths to the different vertices of the hexagon:

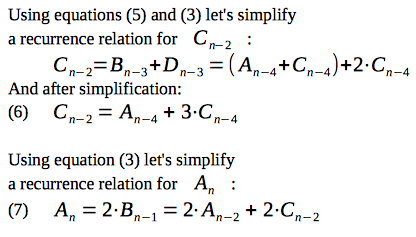

Now, our goal is to reduce an amount of variables inside the recurrence relations:

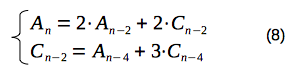

So, we have obtained a system of two recurrence relations: (6) and (7), with two variables:

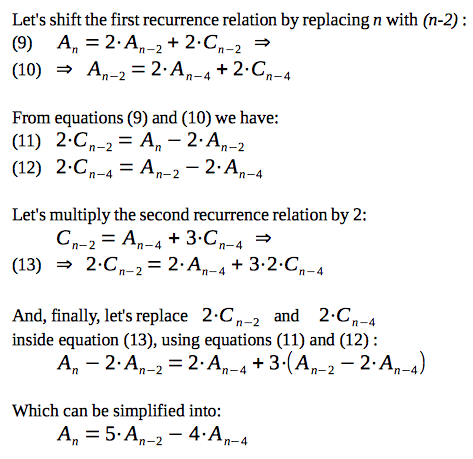

Now, let's derive the recurrence relation for amount of paths, which end in the vertex "A" after n moves:

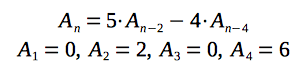

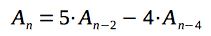

So, finally, we have derived a neat recurrence relation for calculation of the amount of paths, which end in the vertex "A" after given amount of moves.

I would like to show its formula once more, together with solutions for the base cases (when N is 1, 2, 3 or 4):

You can verify by hand the correctness of the derived recurrence relation, using the table with solutions, which was presented in the previous section of the post.

Using the derived recurrence relation, we can implement very simple non-recursive solution:

int solve(int moves) {

if(moves == 1) return 0;

if(moves == 2) return 2;

if(moves == 3) return 0;

if(moves == 4) return 6;

// Sliding window, which spans over:

int a_n_1 = 6; // A(n-1)

int a_n_2 = 0; // A(n-2)

int a_n_3 = 2; // A(n-3)

int a_n_4 = 0; // A(n-4)

for(int i = 5; i <= moves; i++) {

// Calculate a new item of the sequence:

int a_n = 5 * a_n_2 - 4 * a_n_4;

// Shift the sliding window:

a_n_4 = a_n_3; // A(n-4) <- A(n-3)

a_n_3 = a_n_2; // A(n-3) <- A(n-2)

a_n_2 = a_n_1; // A(n-2) <- A(n-1)

a_n_1 = a_n; // A(n-1) <- A(n)

}

// Now, the result is inside A(n-1)

return a_n_1;

}However, the runtime complexity of presented algorithm is obviously, still O(N)!

So, why would be bother ourselves with all these derivations, if we still get the linear-time solution?

Well, we have revealed the fact, that the solution of the problem can be expressed in the form of a linear recurrence relation of the 4th order with constant coefficients. We can make use of this fact for development of more efficient algorithms.

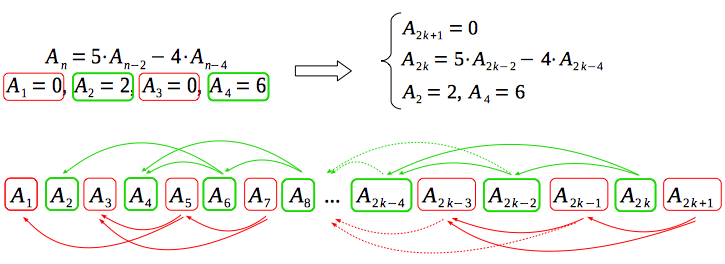

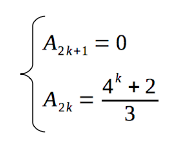

Additionally, based on the discovered recurrence and the principle of induction, we can prove, that the solution for odd values of N is always zero:

This observation allows us to solve immediately the problems with odd values of N (solution is always zero),

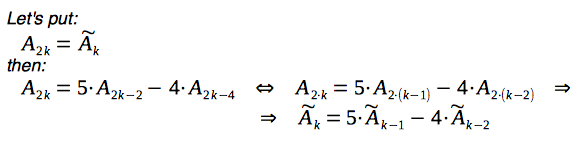

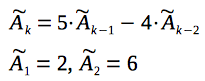

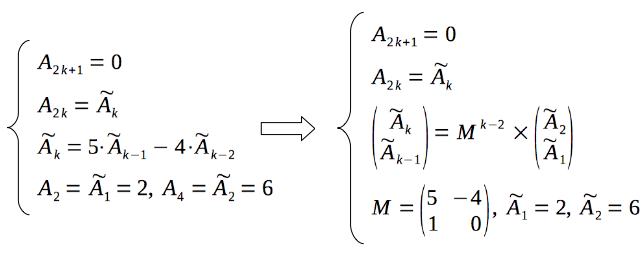

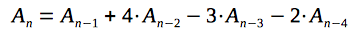

and for instances of the problem with even values of N we can transform the 4th-order recurrence relation into the 2nd-order recurrence relation:

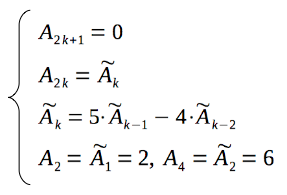

So, here is a full description of solution, based on the 2nd-order recurrence relation:

Now, before moving to the more optimal algorithm, let's implement the simpler version of O(N) solution, based on the derived 2-nd order recurrence:

int solve(int moves) {

if(moves % 2 == 1) return 0;

int k = moves / 2;

if(k == 1) return 2;

if(k == 2) return 6;

// Sliding window, which spans over:

int a_n_1 = 6; // A(n-1)

int a_n_2 = 2; // A(n-2)

for(int i = 3; i <= k; i++) {

// Calculate a new item of the sequence:

int a_n = 5 * a_n_1 - 4 * a_n_2;

// Shift the sliding window:

a_n_2 = a_n_1; // A(n-2) <- A(n-1)

a_n_1 = a_n; // A(n-1) <- A(n)

}

// Now, the result is inside A(n-1)

return a_n_1;

}As you can see, provided O(N) solution is much more concise than Dynamic programming-based solution with the same runtime complexity.

Now, it is time to develop an algorithm with better runtime complexity.

O(log(N)) solution using generating matrix and exponentiation by squaring

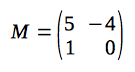

We will continue to work with the recurrence relation, derived in the previous section:

Now, let's consider a column-vector of two consecutive values of this recurrence relation:

Also, let's consider a matrix, which contains coefficients of the recurrence relation in the first row (and the second row, constructed in a special way):

Now, let's multiple given matrix and the column-vector:

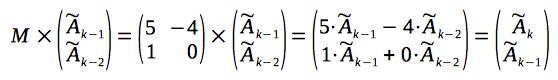

As a result of multiplication we have obtained a column-vector, which contains a new value of the recurrence relation:

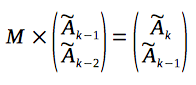

You can see, that the new column-vector also contains two consecutive values of the sequence. So, in order to produce the next value of the recurrence relation, we can multiply it with a matrix again:

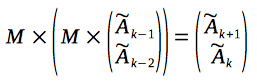

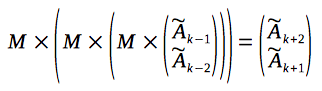

We can multiply the column-vector with a matrix once more, in order to obtain a next value, and so forth:

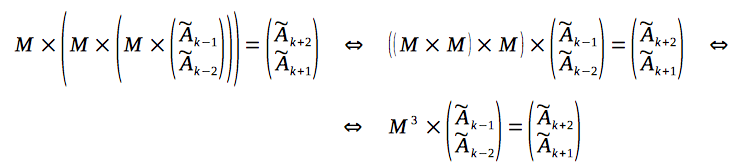

Now let's rewrite the considered equation, according to the associativity property of the matrix multiplication:

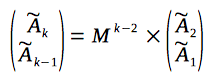

So, based on induction, we can prove, that for calculation of the k-th item of the sequence - it is needed to multiply the column-vector (which consists of the two initial items of the recurrence) with a (k-2)-th power of the matrix:

Can we calculate the N-th power faster than O(N)?

Yes, we can! Let's make use of the Exponentiation by squaring technique in order to obtain the result within O(log(N)) steps.

So, now the solution can be expressed in a following form:

Below is code snippet with implementation of the described solution. The code is not so concise as previously, however this approach allows to solve large instances of the problem.

int solve(int moves) {

// For odd values of moves

// solution is always zero

if(moves % 2 == 1) return 0;

int k = moves / 2;

if(k == 1) return 2;

if(k == 2) return 6;

// Solve with O(log(N)) complexity

int[][] Mn = power_M(k - 2);

int a2 = 6;

int a1 = 2;

int result = Mn[0][0] * a2 + Mn[0][1] * a1;

return result;

}

// Calculate n-th power of generating matrix

int[][] power_M(int n) {

int[][] result = new int[][]{ {5, -4},

{1, 0} };

power(result, n);

return result;

}

// Exponentiation by squaring

// O(log(N)) complexity

// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exponentiation_by_squaring

void power(int[][] X, int n) {

if(n == 1) {

return;

}

if(n % 2 == 0) {

multiply(X, X);

power(X, n / 2);

} else {

int[][] initial = { {X[0][0], X[0][1]},

{X[1][0], X[1][1]} };

multiply(X, X);

power(X, (n - 1) / 2);

multiply(X, initial);

}

}

// Multiplies AxB and writes result to A

// A and B are 2x2 matrices

void multiply(int[][] A, int[][] B) {

int r_0_0 = A[0][0] * B[0][0] + A[0][1] * B[1][0];

int r_0_1 = A[0][0] * B[0][1] + A[0][1] * B[1][1];

int r_1_0 = A[1][0] * B[0][0] + A[1][1] * B[1][0];

int r_1_1 = A[1][0] * B[0][1] + A[1][1] * B[1][1];

A[0][0] = r_0_0;

A[0][1] = r_0_1;

A[1][0] = r_1_0;

A[1][1] = r_1_1;

}Described approach is a well-known technique, and you can find more details about it in the following resources:

- Matrix difference equation

- Math.StackExchange: Converting recursive equations into matrices

- Matrix Exponentiation

- Solving Linear Recurrence for Programming Contest

- Math.StackExchange: Generating matrix for a recurrence relation

- Stackoverflow: Generating matrix for a recurrence relation

Closed-form solution using characteristic polynomial

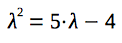

In this section we will continue to work with the recurrence relation, derived in one of the previous sections:

Let's construct a characteristic polynomial for the given recurrence relation:

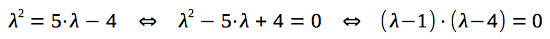

In order to find the closed-form solution, we need to solve given equation:

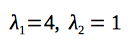

So, the roots of characteristic polynomial are:

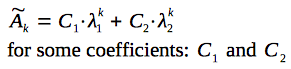

According to the properties of linear recurrence relations, the closed-form solution has the following structure:

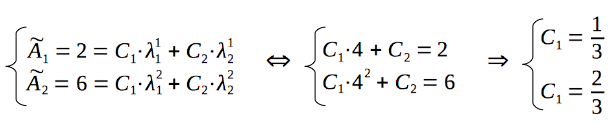

Let's find the coefficients, using the values of the first items of the sequence:

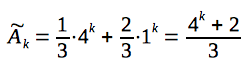

So, the closed-form formula for the n-th item of the sequence, defined by our recurrence relation, is:

Hence, here is a final and very short solution of the problem:

And here a final implenetation of solution of the problem:

int solve(int moves) {

if(moves % 2 == 1) return 0;

int result = ((1 << moves) + 2) / 3;

return result;

}Frankly speaking, due to the need of calculation of the k-th power of number 4 - from the theoretical perspective, the solution still has complexity O(log(k)), however let's leave these details away and enjoy the neat formula, which we have just derived :-)

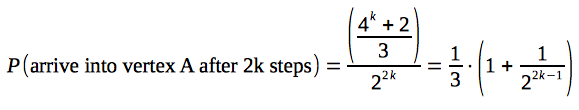

Additionally, the derived formula is convenient for computation of analytical properties of the solution. For example, we can calculate the probability, that after large amount of steps, traveller will arrive into the vertex "A" (of course, we are interested only in even amounts of steps):

- Total amount of possible paths within 2k steps is:

(we are rising the number 2 to the power of 2k - because on each of 2k steps, traveller can choose either of two adjacent vertices)

(we are rising the number 2 to the power of 2k - because on each of 2k steps, traveller can choose either of two adjacent vertices) - Hence, the probability to arrive into vertex "A" is:

Which means, that with a probability approximately 0.33 traveller will arrive to the initial vertex after large amount of moves.

As you can see - the closed-form solution is very convenient for the further analysis, and allows to reveal additional insights about the problem.

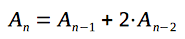

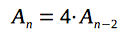

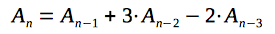

Recurrence relations for other kinds of polygons

So far we have discussed only the neat recurrence relations for the hexagon, but what about other kinds of polygons?

Well, we were able to reduce the complexity of the solution, but we have lost the universality of the developed solutions - it turns out, that for each kind of polygon we need to derive its own linear recurrence relation.

I have derived linear recurrence relations for a couple of different kinds of polygons, and below is provided a table with recurrence relations for the various kinds of polygons:

| Type | Recurrence relation | |

|---|---|---|

| 3 |  |

|

| 4 |  |

|

| 5 |  |

|

| 6 |  |

|

| 7 |  |

|

For me it is still an open question, whether there are any pattern with respect to the structure of the derived recurrence relations (it would be good to have a possibility to obtain a recurrence relation, skipping the boilerplate derivation routine).

Conclusion

- Is a fastest way to tackle the problem

- Can be implemented for different kinds of polygons (not only a hexagon)

- Has exponential runtime complexity

- Hence, sufficient only for the small instances of the problem

Dynamic programming based solution:

- In case, when brute-force solution depends on solutions of overlapping subproblems - it can be transformed into the Dynamic programming solution

- Can be implemented for different kinds of polygons (not only a hexagon)

- Has linear runtime complexity

- Hence, can be used for solving the large instances of the problem

More efficient algorithms require an information about additional aspects of the problem - which limits the scope of the developed solution (for every type of a polygon - we will need to design its own solution):

- We are lucky, that for the given kind of problem it is possible to derive a linear recurrence relation

- Generating matrices and exponentiation by squaring - allows to design

O(log(N))solution - Derivation of the closed-form solution leads to the most fruitful results, however requires more efforts in comparison to the previous approaches

- Having the closed-form solution, we can investigate the various interesting properties of the problem

- Mathematical induction is a useful tool for proving the various properties of designed solutions

Source of the problem

The problem and its closed-form solution were discussed during one of the practical lessons of the course Modern combinatorics, taught by Andrei Mikhailovich Raigorodskii and Dmitriy Gennadievich Ilyinskiy.